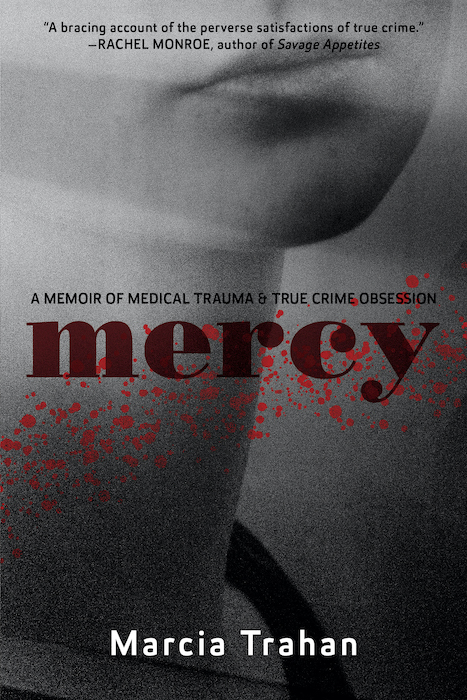

Marcia Trahan's Mercy

It was a pleasure speaking with Marcia Trahan about her compelling new book, Mercy: A Memoir of Medical Trauma and True Crime Obsession, which publishes this week from Barrelhouse Books.

About the Book

When Marcia Trahan began watching true crime television, she did so in secret. She felt ashamed by her fascination with these violent stories, and how hungrily she consumed one gruesome tale after another. Only years later did she start to connect the dots between her true crime obsession and the series of invasive medical procedures that had left her feeling victimized and violated.

Can the body tell the difference between an attacker’s knife and a surgeon’s? This is the central question in Mercy, a question that leads Trahan to re-examine her body’s reaction to lifesaving medical treatment, the childhood experiences that first made her feel unsafe in her own skin,and the true crime genre’s most common tropes.

Part searingly honest memoir, part incisive cultural criticism, Mercy explores the appeal of true crime and the way so many of us live our whole lives bracing for an attack.

Erin Khar: You open the book discussing your true crime obsession, which, as you note, has become an obsession for so many women in recent years, often because true crime allows women to work through trauma. Do you think that the collective cultural draw in the past few years to true crime allowed you to investigate trauma in a way you hadn’t permitted yourself to do before?

Marcia Trahan: The culture's desire for true crime stories became insatiable at just the right time for me. In 2009, when I was trying to process my medical experiences, true crime TV programs were everywhere—it would have hard to avoid them, and indeed, I didn’t want to avoid them. I was powerfully drawn to them for reasons I didn’t initially understand. The medical realm gave me the unspoken but unmistakable message that I should simply be grateful for lifesaving care. At times, I did feel what might be considered appropriate gratitude. But mostly, I was angry, and I didn’t understand why. I knew that my obsession with true crime was somehow connected to medicine, but I didn’t think of my medical experiences in terms of trauma. If asked to describe these experiences, I would have called them “difficult” or “stressful,” but not traumatic. I would have minimized them.

It took me several years of binge-watching true crime TV before I understood that I was drawn to violent stories because my body had experienced medical procedures as violence.

At that point, I realized that the word “trauma” applied to what I had been through. I don’t think I would have recognized any of this if I hadn’t watched hour after hour of murder tales and hadn’t tried for years to puzzle out why I was so obsessed. So yes, the culture’s heightened interest in true crime led to an enormous increase in true crime programming, which in turn allowed me to explore and to identify my trauma.

EK: At what point did you know you were writing a memoir about the intersection between true crime and the medical traumas you’d endured?

MT: I began the memoir as a straight-up illness story. A few years after I made the connection between medicine and violence, and a few years into the writing of the book, true crime started to creep into the narrative. I had resisted it because I didn’t want the book to become lurid, but the topic started showing up anyway, and I finally allowed it in. I began to write about how, for me, watching true crime was linked to medicine; I kept it on a personal level for some time. Later, I wrote about true crime in the context of the broader culture and discussed which aspects of the genre are potentially helpful to women, like offering a way to process trauma, and which are harmful, like blaming female victims for the crimes committed against them.

EK: As someone who has also written about trauma, I know how emotionally and physically draining it can be. What was the writing and editing process like for you? And did you feel like you gained any additional insight after going through revisions?

MT: Yes, confronting trauma is exhausting! For me, the research was the most difficult part. It was painful to pore over my medical records, to read cold, clinical descriptions of surgeries and procedures that made the patient—me—into an object, with my personhood stripped away. It was difficult to go over journal entries from the time of my treatments and see all of the anger and terror I had struggled with. And then working in details from this research was also painful. To depict trauma, I had to relive it.

With all of that being said, writing and editing this book was the most thrilling experience of my life.

Editing was particularly exciting because I could see the book taking shape, becoming something much more interesting than the straightforward story I had originally envisioned. And finding the words to precisely describe trauma is exhilarating.

So often, women’s stories of being harmed are discounted. Using specific language to depict harm and healing gives these stories a chance to be heard. I understood all of the hurt and the blessings of my life in a new way once I finished the book. The pain, the fear, the anger, and the strength are all part of me, and they cohere in my mind as they never had before.

EK: What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received? What’s the worst?

MT: I actually got both the best and the worst writing advice from the same writing instructor! I was in an MFA program and struggling to write personal essays, and this instructor told me to imagine I was writing for The New Yorker, which gave me the literary equivalent of stage fright. But he told me something else I’ve never forgotten: When I was trying to find a way to depict my clinical depression, he wrote in the margin of one of my failed attempts, “Write about the shame.” It was such a simple statement and exactly what I needed to hear. So here I am, 20 years later, having spent five years writing a memoir that exposes nearly everything I’ve ashamed of, plus everything I’m proud of.

EK: What are you reading now?

MT: During the pandemic, I’ve found myself drawn to books about grief. I don’t personally know anyone who’s died of COVID-19, but I couldn’t possibly be unaffected by the enormous loss of life in this country and the world. I’m currently rereading The Still Point of the Turning World by Emily Rapp, a beautiful memoir about what it’s like to mother a dying child. It’s a deep meditation on life and mortality, tragedy and survival.

Marcia Trahan is the author of Mercy: A Memoir of Medical Trauma and True Crime Obsession (Barrelhouse Books, 2020). She earned a master of fine arts in writing and literature from Bennington College. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Rumpus, Catapult, the Brevity Blog, Fourth Genre, apt, Clare, Anderbo, Blood Orange Review, Connotation Press, Kansas City Voices, and the LaChance Publishing anthology Women Reinvented: True Stories of Empowerment and Change. Marcia lives in South Burlington, Vermont, with her partner, Andy, and their crazed feline companion, Bela.